Sleep is universal and essential: not only humans, but even flies and jellyfish sleep for a significant portion of the day. Like eating or mating, sleep is also controlled by motivational drives. Our drive to sleep increases as the need builds up and resets once it is satisfied. But what actually tells us that it's time to sleep?

Prof. Anissa Kempf at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, has long been interested in how sleep drive is generated in the brain. In earlier work in the fruit fly, she identified a molecular sensor, which helps the fly decide when it’s time to sleep. Until now, however, it was unclear in which sleep-control neurons this mechanism specifically operates. In this new study, Anissa Kempf and her team identify the specific sleep-promoting cells in which this sensor acts.

Protein works like a sensor

The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster exhibits sleep behavior comparable to that of humans, making it an ideal model organism for studying sleep and wakefulness. Staying awake requires energy and leads to an accumulation of metabolic by-products inside cells, so-called free oxygen radicals. These oxygen species are a sign of stress at the cellular level, and their levels increase with prolonged wakefulness.

A key player linking these changes to sleep is a protein called Hyperkinetic. “In earlier work, we showed that this protein acts as a sensor: it helps neurons detect the metabolic shift and translates it into changes of neuronal activity,” explains Kempf. “In simple terms, the protein Hyperkinetic tells specific neurons when it’s time to rest.”

Making the picture clearer with more precise tools

In recent years, scientists have learned that some widely used methods for targeting specific fly neurons can also affect other sleep-related cells nearby. This made it harder to know exactly where the sleep-promoting effect was coming from. In this new study, her team used more precise genetic tools to separate these cell populations and test them independently.

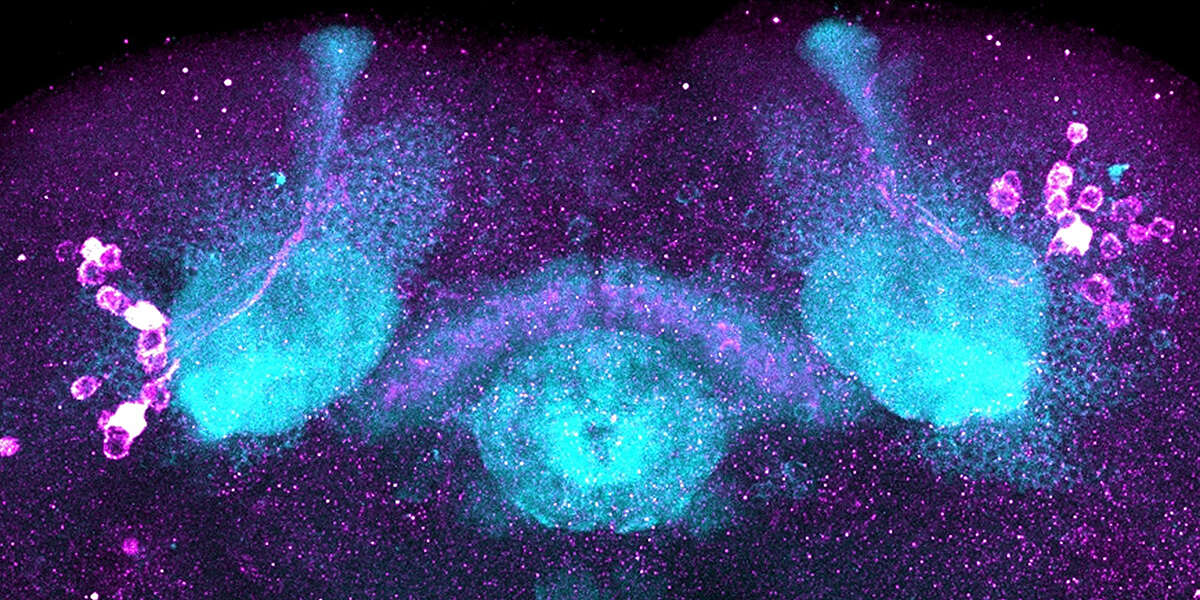

These tools allowed them to identify the sleep-promoting cells, to precisely localize where the stress-sensing mechanism operates, and to show that it promotes sleep. Importantly, this mechanism is highly specific to so-called fan-shaped body neurons, suggesting a targeted and specific mechanism for sleep control.

Novel insights into sleep control

This study demonstrates that the brain is not just counting hours awake. It is actively measuring the biological cost of wakefulness. As energy is used and oxidative stress increases, sleep-promoting neurons receive a signal that recovery is needed.

Although the research was done in fruit flies, the principles of sleep control are broadly relevant. From flies to humans, all animals must balance periods of activity with rest. By uncovering where and how even a simple brain measures sleep pressure at the cellular level, the researcher shed new light on why sleep becomes unavoidable after prolonged wakefulness.

Publication:

Alexandra M. Medeiros, Hugo Gillet, Shani Kornhäuser, Paul Dampenon, Ammerins de Haan, David Ruel and Anissa Kempf. A Hyperkinetic-dependent redox-sensing mechanism operates specifically in dorsal fan-shaped body neurons to promote sleep. Current Biology; published online 19 January 2026

Contact: Communications, Katrin Bühler