The G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) perform very diverse tasks in our body. They enable us to see, taste food, feel cold or warm, or respond to stress. Located on the cell surface, GPCRs sense a large variety of signals such as nutrients, light, odors or hormones. By changing their conformation, they transmit this information from the outside to the inside of the cell. The accumulated knowledge about GPCRs has tremendously affected modern medicine: about one-third of all marketed drugs target GPCRs.

Empty spaces important for receptor activation

Using cutting-edge NMR technology, the research team led by Prof. Stephan Grzesiek, together with collaborators at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel and the Paul Scherrer Institute, has now discovered that GPCRs contain completely empty cavities which are important for their activation. Their recent, experimental approach, published in “Nature Chemistry”, may direct and speed up the search for new and more specific drug candidates with fewer side effects.

Model receptor to study general GPCR function

Although the 826 GPCRs within the human body respond to many different stimuli, they all share a common architecture. “Our aim is to understand at the atomic level how GPCRs transmit signals,” says Dr. Layara Abiko, who co-directed the study. “For many years, we have therefore been studying the β1-adrenergic receptor, a GPCR that prepares the body for fight or flight.” The hormone adrenaline binds to and activates the receptor which triggers a stress response, for example, causing an increase in heart rate and blood pressure.” Beta-blockers inhibit this receptor and thus are effective drugs to treat hypertension or cardiovascular diseases.

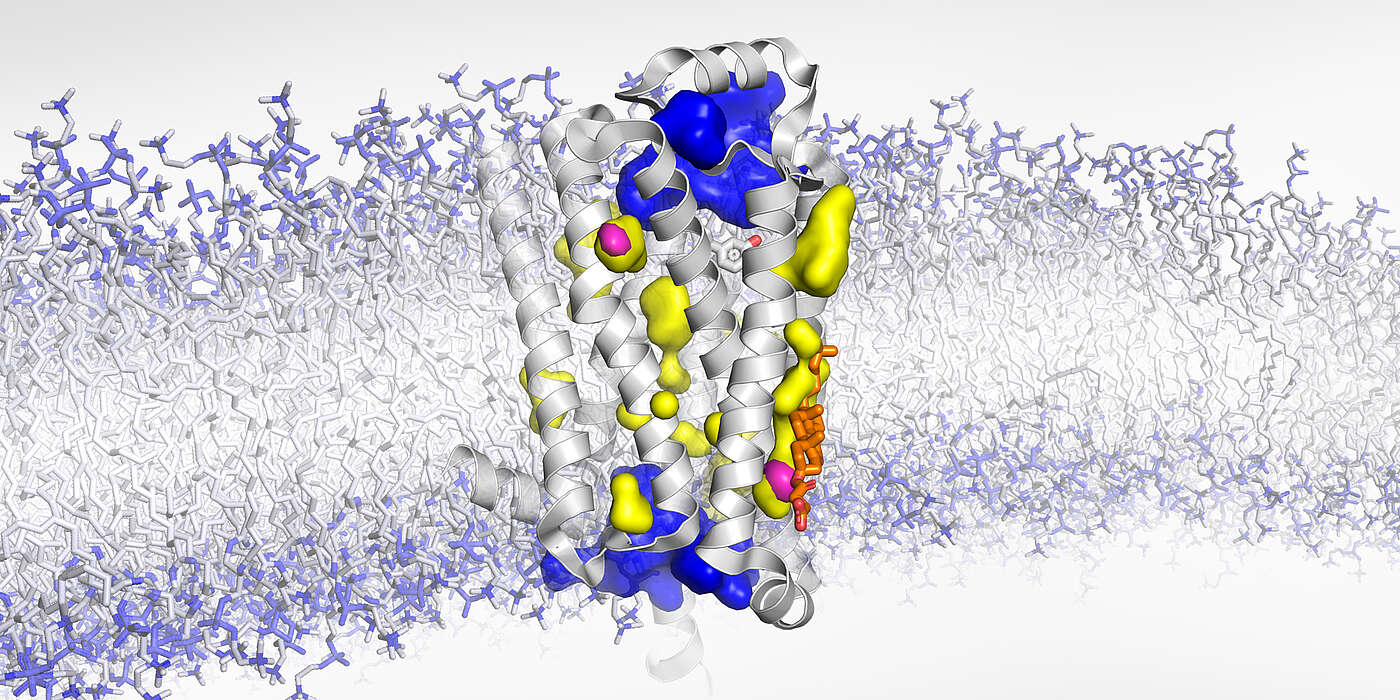

Exact localization of dry voids

“Thanks to high-pressure NMR and our experimental approach using X-ray scattering on receptor crystals that incorporated the noble gas xenon, we could further complete the picture of this highly dynamic receptor,” says Abiko. ”Previously, it was assumed that the cavities inside the receptor are filled with water. We have now revealed that some of them are empty.” During activation, the conformation of the receptor changes in such a way that these dry voids get compressed and disappear. Consequently, the receptor shrinks just like when you squeeze a sponge. In case of the β1-adrenergic receptor, this conformational change is key for initiating the body’s fight-or-flight response.

The researchers have now been able to exactly localize two of such empty cavities and revealed that cholesterol – an important cell membrane component – can fill one of these. Like a wedge, cholesterol impedes the receptor from squeezing and changing to its fully active state. “Blocking this void obstructs the subtle, but essential movements required to activate the GPCR,” explains Abiko. “We think, this wedge effect could be another layer of receptor regulation.”

New routes for drug development

But why can scouting for dry voids be important? Classical drug binding sites are often similar among GPCR subclasses. A drug directed to such a site may bind to more than one receptor and therefore cause unwanted side effects. In contrast, the dry cavities differ considerably between GPCRs, even when they are from the same subclass. This makes them highly selective drug targets.

“In this way, you may design drugs that are highly specific for one receptor”, explains Abiko. The developed new approach may locate such unconventional drug binding sites which differ strongly between the receptors. This can help the screening process for new therapeutics, save time and reduce costs.

Original article:

Layara Akemi Abiko, Raphael Dias Teixeira, Sylvain Engilberge, Anne Grahl, Tobias Mühlethaler, Timothy Sharpe, and Stephan Grzesiek. Filling of a water-free void explains the allosteric regulation of the β1-adrenergic receptor by cholesterol. Nature Chemistry, published online 11 August 2022

Contact: Communications, Katrin Bühler